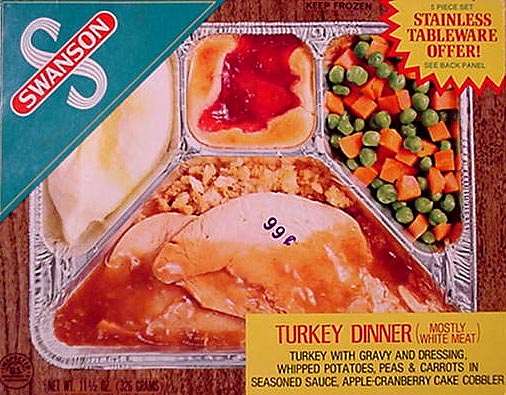

There’s something so deliciously nostalgic and perfect about an old-school TV dinner, right? That quintessential aluminum tray with the little divided sections and the perfectly portioned, homey little meal ready to go in about 45 minutes. It was like a mini miracle of convenience, arriving right in time to plop down in front of boob-tube and watch the latest episode of “I Love Lucy.” Hence the name, “TV Dinners.” They were meant to be eaten with your favorite TV friends.

But here’s the thing: while those frozen dinners started out as a comforting solution for busy families, they ultimately opened the door to something much more sinister. Did TV dinners quietly set America down a path of highly processed, nutritionally bankrupt food choices? Many believe that’s exactly what happened.

However, like any good story, we need to go back to the beginning.

The golden age of TV dinners was all about simplicity served in a pre-portioned tray.

When the TV dinner made its debut in 1953, it was nothing short of a sensation. The original Swanson meal boasted (yes, I said boasted) a turkey dinner with cornbread stuffing, peas, and a dessert. And, honestly, at the time, it was revolutionary.

At a time when women were entering the workforce and time was in short supply, these little trays of food provided something valuable—relief. Dinner was taken care of in a snap, and you didn’t need a culinary degree to get it on the table.

But this shift also marked the beginning of the end for traditional family meals around the table. Instead, Americans moved to the living room, TV trays in hand, settling in for their favorite shows. Seems harmless enough, right? But this casual change had deeper, more emotional consequences that we’d only start to feel years later.

The early TV dinners were almost a balanced meal: protein, veggies, starch, and even dessert, all neatly packaged into a single serving. This little convenience was a life raft for busy families—a way to still gather for dinner without the mess or fuss.

But as we all know, nothing stays simple for long.

We went from balanced to bloated, real fast.

As time went on, the portions grew, the fat content skyrocketed, and suddenly, those once-modest TV dinners were looking more like unhealthy indulgences than balanced meals. What started as a reasonable solution turned into an entire food category that embraced more is more, and that’s when things really began to unravel.

It wasn’t just that the portions increased—it was that the sodium, preservatives, and added sugars crept in and up, too. Research shows that many modern frozen meals now contain nearly half a day’s worth of sodium in a single serving, and let’s be honest, that’s not exactly the health win Swanson probably envisioned back in the ‘50s.

Or was it?

Was it the TV dinner that first tempted us down the dark path of processed foods? While we can’t blame a single meal for a nation’s terrible eating habits, it was undoubtedly the gateway drug—the first step toward a culture that prized convenience over quality. A running theme that has plagued modern US society from “fast fashion” to “fast food.” It was quick, easy, and marketed as the ultimate solution to a problem many didn’t even know they had.

And that’s where the marketing comes into play. The TV dinner had some big hits and some legendary misses, but in the end, they reshaped how we eat and interact.

For the most part, the marketing and advertising behind TV dinners was nothing short of genius. It tapped into a cultural moment when women were entering the workforce en masse, juggling jobs and home life, and the message from Shannon and others was simple: they didn’t need to choose between being a career woman or a homemaker—they could do both, with a little help from the frozen food aisle.

Studies from the 1970s show that advertising heavily pushed the narrative that busy families had “no choice” but to embrace prepackaged meals.

It was either turn to processed foods, or be left in the dust. The message was that convenience was king, and if you didn’t have time to cook a full meal every night, well, here was your saving grace—a processed turkey loaf made of “mostly” white meat.

But here’s the burning question: was this really a choice? Or was it a clever way to sell a product that was, at best, a quick fix and, at worst, a long-term health hazard? By the 1980s, ultra-processed foods made up nearly 60% of the American diet, and it’s no coincidence that the rise of TV dinners and frozen meals played a huge part in that.

So, as Americans traded the dining room for TV trays and swapped out porcelain plates for aluminum, they were also making a bigger choice: sodium-packed, preservative-laden “factory food” over wholesome, home-cooked meals. This wasn’t just a trend—it was the birth of an entirely new food category, one that was high in fat, salt, and sugar and—many argue—designed to be addictive.

UTMB Health:

Can children become “addicted” to processed foods? This is an important question and the answers are important and scary. The World Health Organization has declared that there is a global epidemic of obesity. This is more than a cosmetic issue. It’s an important health issue causing numerous chronic health problems, pain, and earlier than expected deaths.

The increase in obesity is linked to the availability of varied, delicious, and fattening foods. A comprehensive review in Nutrients in 2019 discusses the question of why some individuals are able to resist overeating while others cannot. By understanding cravings, problems with overeating, and loss of control better treatments can be developed.

While food is not yet recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as addictive, it’s a subject of ongoing research and debate. Experts argue that certain individuals may exhibit addictive-like behaviors and neurobiological changes related to food. Much of the research in understanding addiction is evolving. Gearhardt et al in the British Medical Journal discusses how ultra-processed food high in carbohydrates and fats are addictive substances.

Using the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) they have found that not all foods have addictive potential. It has also been found that intake of processed foods with high levels of refined carbohydrates or added fats, such as sweets and salty snacks, are addictive. These types of foods are most strongly implicated in behaviors of addictions such as excessive intake, loss of control over consumption, intense cravings, and continued use despite negative consequences. It has been found that refined carbohydrates or fats cause similar levels of dopamine in the brain as measured with additive substances such as nicotine and alcohol.

Refined carbohydrates come from the processing of the grain by removing the bran and germ of grain. What is left is less nutritious and more “addictive”. Ultra-process foods (UPF) include packaged snacks, sugary drinks, fast food, frozen meals, breakfast cereals, and many prepackaged desserts. UPF’s are absorbed quicker and hit the brain releasing dopamine quicker. This is a quick “fix”.

Whether food is not defined officially as addictive certain ingredients suggest they can cause an addiction disorder. Research has and will help develop treatments for intense cravings and overeating.

As I suggested earlier, TV dinners marked the slow collapse of the family dinner. Who had time to sit down and ask Susie about her day at school or check in on Bobby’s latest girl drama? Heck, “Sonny and Cher” was on TV, and there was a Swanson fried chicken Hungry Man dinner in the oven.

By the 1970s, the marketing game had also changed. It wasn’t just about meeting the demands of a busy lifestyle anymore—it was about feeding your cravings. Food became “comfort” and an emotional experience. So why not grab that giant Hungry Man, plop down in front of “Barnaby Jones,” and fill up your stomach… and your soul too?

And here’s the twist: research shows that eating in front of the TV not only ups your caloric intake, but it’s also a fast track to obesity. So, while you’re zoning out on your favorite show, you might be mindlessly packing on more than just extra helpings.

Scientists have long known that our wider environment plays a crucial role in our diets, and there’s a wealth of research showing a link between watching TV and a higher risk of obesity, largely due to lower levels of exercise that come with such sedentary behaviour.

But watching TV may also be affecting how much we eat too. Being distracted is one of the leading theories behind why we might eat more while watching TV at the same time, says Monique Alblas, assistant professor of communication science at the University of Amsterdam.

This could be because, when we’re sucked into a riveting plot, we have less attention available for eating so we’re not aware of the bodily signals telling us we’re full, which could lead to overeating. There’s also research suggesting that we don’t remember what we’ve eaten when we’re consuming food front of the TV and struggle to accurately estimate the amount we’ve eaten, which could mean we eat more later on.

Alblas has found that people spend longer eating when they’re watching TV at the same time.

She used already existing data collected by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research, for which people were asked to keep a diary of everything they did over a week, including eating and watching TV, and even what type of TV programmes they were watching.

When Alblas analysed the data, she found that the people spent longer eating when they were watching TV at the same time.

They also found that that the total time they spent eating was longer on days of concurrent TV-watching and eating at the same time, compared with days of eating without simultaneously watching TV, which she says suggests they didn’t realise how much they were eating because they were distracted.

The findings themselves don’t show that people ate more, necessarily, or what food they ate exactly, as the only thing they recorded was the length of time spent eating. Of course, as the results are self-reported, if people were losing themselves in a particularly good plot, they may have also just misremembered how long they had been eating for.

But, Alblas says, there’s existing research showing that time spent eating is correlated to eating more calories.

New studies show that a vast majority of millennials prefer cooking at home over ordering takeout or eating frozen meals, which is a pretty stark contrast to the ‘convenience craze’ that defined the mid-20th century. So what changed?

Maybe it’s because we’ve finally realized that convenience came with a hidden price. The rise of heart disease, diabetes, and obesity has put our food choices under a microscope, and it’s become impossible to ignore the role ultra-processed foods have played in all of that. We’re starting to see that it wasn’t just about time-saving; it was about marketing a lifestyle that led us straight into the arms of health issues we’re still trying to shake today.

The TV dinner—a symbol of comfort and convenience—helped reshape America’s food landscape, but at what cost? It wasn’t just about dinner in 45 minutes; it was about the slow, steady shift toward a reliance on processed foods that prioritized profit over nutrition. Marketers decided what we wanted long before we even knew we wanted it.

And now? Well, we’re paying the high price of convenience, with fractured connections and health struggles that we’re still trying to untangle.

But maybe there’s a silver lining. As more families move away from processed meals and back toward whole, homemade foods, there’s hope for a healthier future. The question is: how long will it take us to fully undo the damage that began with a tray of turkey, peas, and stuffing?

Till next time, be wickedly wonderful.

It’s an individual choice: Do you want food that was grown, or manufactured?

I love TV dinners. I can put one in the oven when I’m alone out at our rural property, go out and work for another 40 minutes, and when I come back in there’s a delicious hot meal ready for me. I’m almost 70, in perfect health, 6 foot 1, 190 lbs.

My wife and I almost always eat in front of the TV. We dont have kids to interview about their day, she’s retired and I work from home. We have said about all we need to say through the course of the day. We dont eat more because of it, we put our portions together, often separating enough for leftovers for another meal and thats what we eat. How are people eating more? Do they take the entire pan of lasagna to the living room with them and eat directly out of it?

Prepared meals are more expensive, for any that actually taste good. I didn’t grow up eating them because my mom was budget conscious, and TV dinners didn’t fit the budget.To me that was the kind of food the rich kids got to eat. For some people who refuse to learn to cook, like bachelors living alone, they probably have better nutrition due to frozen meals.

The only solution to both Global Warming and inequality is, Soylent Green for all.